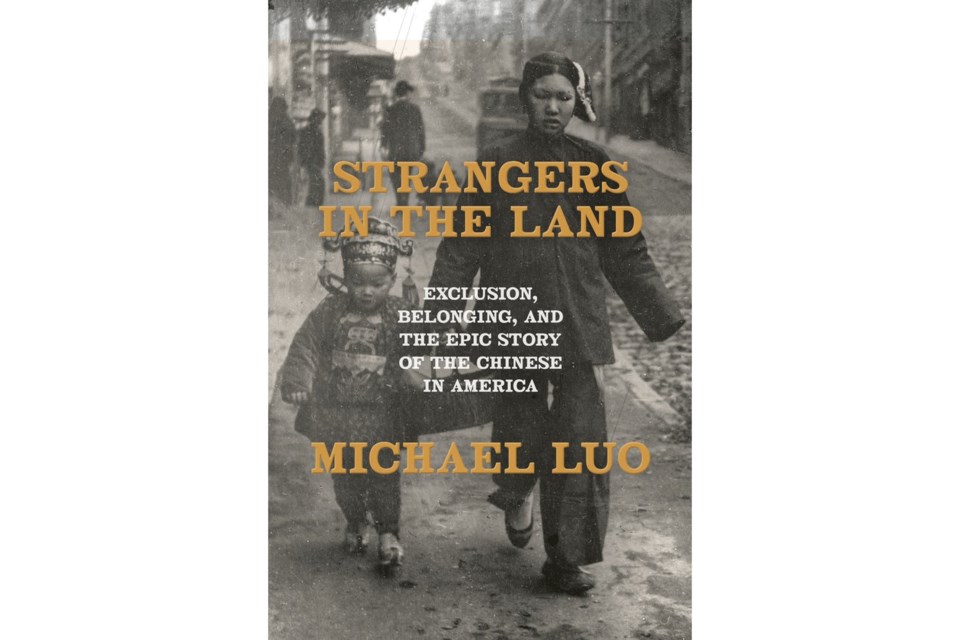

The history of in America has always been about much more than one particular ethnic group. As Michael Luo’s “Strangers in the Land: Exclusion, Belonging and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America” demonstrates, understanding America’s efforts to keep Chinese laborers out, and the violence enacted against those who stayed in, is essential to understanding the evolution of as we know it today.

That’s because restrictions against Chinese immigrants represented the first major flex in the modern era of the federal government’s power to control its borders. Chinese laborers were the first group to be barred from the entire country based on national origin, and lawsuits involving this group were often major tests of constitutional liberties — most notably the Supreme Court case of Wong Kim Ark in 1898, which established the right to

Time and time again, the treatment of this minority group served as a test of America’s ability to live up to its own ideals of equality. As Massachusetts Sen. George Frisbie Hoar noted when he spoke out against the exclusionary legislation of the 1880s: “We go boasting of our democracy, and our superiority, and our strength. The flag bears the stars of hope to all nations. A hundred thousand Chinese land in California and everything is changed.... The self-evident truth becomes a self-evident lie.”

Luo’s book covers over a century of history, from the 1840s to 1965. Immigration from China was largely unfettered at first, and Chinese laborers were essential to building the — a truly epic part of the story, with thrilling descriptions of how men dangled in baskets off 2,000-foot precipices and set off charges that blasted open whole mountains. One witness wrote: “When the debris had ceased to fall, the echoes were still reporting among the distant hills.”

However, unemployment crises in the 1870s led white workers to jump on Chinese labor as the ultimate economic scapegoat. Chinese workers faced near-constant hate and harassment, ranging from the daily humiliation of stone-throwing children to outright massacres by angry mobs. Luo spends chapter after chapter meticulously documenting the disturbing details of 19th-century pogroms and race riots against Chinese communities in places like San Francisco, Los Angeles, Denver and Seattle.

Despite the ugly violence, Luo also takes care to document the actions of good men and women who stood up to the mob. Take Charles Andrew Huntington, a 73-year-old reverend in Eureka, California, who helped stop a massacre against Chinese residents in 1885. He lectured an enraged crowd: “If Chinamen have no character, white men ought to have some.” Fanatics still ran every Chinese person out of town. A Chinese Christian, Charley Way Lum, had stopped by Huntington’s house to pray before he left, when men burst in and put a rope around his neck. Another minister, C.E. Rich, intervened: “If you hang him, you’ll hang him over my dead body.” Lum escaped on a ship to San Francisco.

Anti-Chinese sentiment enjoyed widespread popularity among both parties and played a major role in national politics, as it was considered key to winning the electoral votes of the West Coast. Starting with the Page Act of 1875, Congress started passing Chinese exclusion laws that grew more draconian every year. The Page Act targeted Chinese women, several years earlier than Chinese men, due to the widespread prejudice that most of them were sex workers.

Anti-Chinese fervor culminated in the 1892 Geary Act, which required every Chinese person in the U.S. to register with the government or be deported. Immigration restrictions began to ease only when China became an ally in World War II – showing how much the vagaries of the shifting geopolitical winds can blow back on people at home.

One shortcoming of the book is that Luo devotes so many pages to documenting what was done to Chinese immigrants that there’s comparatively little time spent on what they did for themselves, on who they were as individuals beyond victimhood. A few compelling portraits do stand out: men like Yung Wing, an avid football player and Yale graduate who devoted his life to helping boys from China receive a Western education; Joseph Tape, who fought for his daughter’s right to enter public school in San Francisco; and Mamie Louise Leung of Los Angeles, the first Asian-American reporter to work at a major newspaper.

The fact that Chinese-Americans remained in the United States at all, despite widespread prejudice and the whole force of federal immigration law working to keep them out at every turn, speaks to the incredible tenacity of the community. One anecdote encapsulates this determined spirit: a Chinese coal miner, Lao Chung, was shot during an 1885 attack in Rock Springs, Wyoming. He survived and continued working for decades, the bullet still lodged in his back.

—

Luo was a national writer at The Associated Press from 2001-03 but has not met the reviewer, who joined in 2022.

___

AP book reviews:

Sharon Lurye, The Associated Press